Now this is a conundrum… how to ask a small and simple question about a subject which is so little considered and yet was of such importance to the carriage of goods in the late 19th century… and a subject which was relevant to all railway companies since wagons from most (any?) of those companies could have been seen on the Extended Widened Lines. OK, possibly wagons of the North London Railway might not have penetrated the gloom of those hallowed tracks.. maybe a reader can offer a plausible scenario for NLR wagons working over the EWL?

So to the subject of this post… sheets ands ropes, required in their thousands for covering and protecting goods in transit when carried in open wagons.

Much has been written about how the railway companies managed the movement of loaded and empty wagons…. and about how the Railway Clearing House kept records of foreign* wagon movements between railway companies…. little has been written about the management and return of the sheets and ropes which would have made similar journeys across railway boundaries. A good explaination of how the Midland Railway (and its successors) managed wagon sheets and associated ropes is provided by Midland Record No.3 (Wild Swan)… good enough to prompt investigation into how things were done on other railways. Such a task seems necessary to the working of goods services through Basicilia Fields and yet such a task is onerous in the extreme.

How can readers of this journal assist? Initially, by contributing to what is known and where such information is recorded relating to wagon sheets / ropes for those railway companies whose wagons are likely to form the bulk of the goods stock working over the Extended Widened Lines. Please feel free to provide such details by comments to the Quirky Answers post for this subject. Our initial thoughts are that such wagons are likely to come from the following companies:-

* Great Central Railway;

* Great Eastern Railway;

* Great Northern Railway;

* Great Western Railway;

* London and North Western Railway;

* Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway;

* Metropolitan Railway;

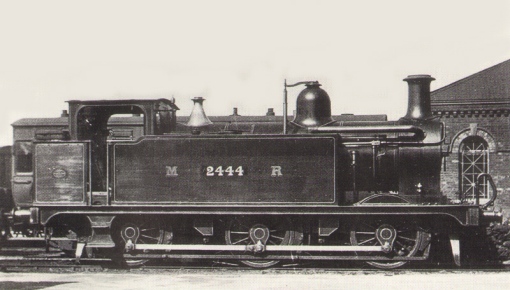

* Midland Railway (recorded in Midland Record No.3).

thank you, Graham

[BTW – information received on this subject is available in “Querky Answers – Sheets and Ropes“]

* foreign in this context means a wagon owned by railway company “A” working over the tracks of railway company “B”.