Or ‘cartage’ by another name.

Basilica Fields is set in the period 1890-1905 at which time options for the transport of goods were limited to canal, rail and road with movement on the road being mostly by ‘horse and cart’. So in the late Victorian era goods traffic was moved between towns (or village, or city, or colliery or dock…) by the railways at a fine pace…and then delivery to customer’s premises would be dependent upon how fast the horse would go whilst pulling a loaded lorry. Whilst the GWR, in common with many other railway companies, used steam lorries for heavy loads, the use of petrol /diesel power for mechanisation of the collection and delivery of traffic was not viable in the Basilica Fields timescale. We prefer to leave such advances to be hidden in the mists of time – or the depths of a London pea-souper.

Back to the topic… This journal has introduced previously the subject of Artillery Lane and the GWR Goods Depot at Gun Street, a small depot which acted as a satellite to the GWR depot which served Smithfield Market. In truth the East End of London seemed to be awash with goods facilities for some of those railway companies which served London – try ‘Town And Country’ Vol. 1, (Irwell Press) for a map showing the coal, grain, potato and general merchandise depots and yards to be found within a few miles of Fenchurch Street station. Artillery Lane is the first part of Basilica Fields to be described in detail so far; there are many more locations to be described in the journal and some of those locations include goods facilities such as coal drops, warehouses and docks…mostly served by the Great Eastern Railway.

Which means that the streets, yards and depots of Basilica Fields will feature a wide range of railway wagons (to carry the traffic to / from the sidings) and an equally wide range of horse-drawn lorries, vans and poles. Each location in Basilica Fields will illustrate the handling of specific traffics and the horse-drawn vehicles will be those appropriate to the traffic and the railway company. So, for example, the traffic which is handled at the Gun Street depot requires horse-drawn vehicles of the type(s) which the GWR developed for it. In addition to the horses and the horse-drawn vehicles, the cartage services dictated that the railway company provided ‘bed and breakfast’ for the horses, and so Gun Street is provided with stables and a provender store – which is cue for two specialised traffics, being provender in and manure out.

As a description of the horse-drawn lorries and vans for Gun Street requires an understanding of the traffic through that depot, then the GWR Cartage Services for Gun Street Depot starts with details of goods received and dispatched.

I’ve been sent a link to a short article illustrated with a number of contemporary photos of the slum children in the East End 100 years ago. The subject isn’t your typical DailyWail Maul Mail fayre (no mention of celebrities…), and by necessity it skims over much of the realities of life with a few factoids chucked in for good measure and shock value. I half-expected “…and this is where we’re heading in 2011…” at the end of the piece, and no doubt one or more will surface sooner or later in the reader’s comments. Edit: Blimey, I should have put some money on that. One appeared even before I’d finished this post…

However, it’s the photos of the children that steal this piece, and their eyes speak volumes.

Further edit: OK, they’ve changed a couple of photos since I posted the above and have employed a reject comedian to rewrite the captions. So much potential for an article, such a waste.

If you’re really interested in the social conditions of Victorian London, then the contemporary Victorian Street Life in Historic Photographs by John Thompson, first published in 1877 and reprinted by Dover Publications in 1994 is a fantastic, and often quite shocking work. Highly recommended.

Victorian Street Life in Historic Photographs

John Thompson

First published 1877.

New edition edition published 1994 by Dover Publications Inc.

ISBN-10: 0486281213

ISBN-13: 978-0486281216

Following the dispersal of the Huguenots and Irish after the collapse of the silk weaving industry, in the middle of the nineteenth century a significant number of Dutch Jews or Chuts settled in the Tenterground area of Spitalfields, bringing with them the trades they practised in Amsterdam such as cigar, slipper and cap making. These tradesman and their families emigrated due to the prejudice which barred them from the guilds in the Netherlands and the slide of the Dutch economy.

Following the assassination of Alexander II of Russia in 1881, 120,000 Ashkenazic Jewish émigrés, mostly impoverished rural workers, fled persecution in Europe and also settled in England. A significant proportion of these refugees gravitated to the East End, often sub-dividing the old Huguenot houses to accommodate as many families as possible, until in some areas Jews accounted for up to 95% of the population. Their vast numbers initially caused much local tension, not only between themselves and the Chuts (whose practices such as eating non-kosher seafood were considered unclean), but with other local communities too.

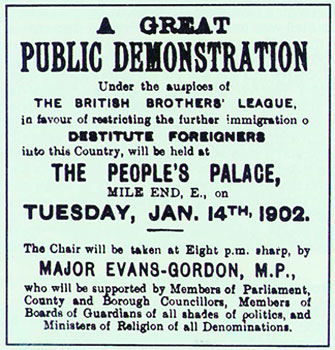

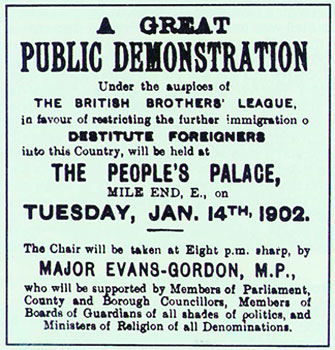

A popular and media backlash ensued, gaining the support of notables and the trade unions which resulted in the formation of the anti-semetic restrictionist group The British Brothers League, the demands of which prompted the government to introduce The Aliens Act of 1905. The Act sought to control immigration by preventing paupers and criminals from entering the country, but also ensured asylum for the religious and politically persecuted.

Before long, mechanised cigarette making machines caused the cigar economy to collapse and the Chuts began to disperse, some returning to Amsterdam, others emigrating to the USA, and some assimilated themselves into the wider Jewish community in the East End.

The language of the Ashkenazim – Yiddish – a High Germanic dialect formed from a fusion of Hebrew, Aramaic, Slavic and Romanic languages, and written in the Assyrian script, soon predominated the area and could be seen in shops, signs, billboards, newspapers and theatres. Food and its preparation was obviously important, and soon shops and markets began to thrive, such as kosher butchers, bakers, fish sellers, general grocers and sundry stores.

Of course religion played an important part in Jewish life, and just as everyone in England lived within the sound of a church bell, synagogues sprang up to tend the spiritual needs and to provide welfare to the living, and chevra kadisha to deal with the practicalities and rituals of the dead.

Old Castle Street synagogue in Whitechapel was a typical example of old housing converted to a place of worship within the Jewish ghetto. The entrance (to the right of the wagon) was an obvious feature, situated as it was within a residential and commercial terrace. Joseph Polowski, a china and glass wholesaler, had his export warehouse to the right, as well as a corner shop beyond the wagon in Wentworth Street (one of the border streets of the Tenterground enclave), in which, incidentally, there were no fewer than fifteen kosher butchers by 1901.