In my original plan, the time-frame for Basilica Fields was going to span the early 1900s to circa 1915, but somewhere along the line I dialled both ends backwards which means that the four classes of engines featuring in this entry will no longer play a part as their presence in an 1890s/early 1900s setting is an anachronism too far, even for my pet cat, Schrödinger. However, one or two of them may make an appearance elsewhere down some diverse branch of the Basilica Fields multiverse (but enough of that wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey stuff for now) so I’ve included them for completeness.

Upon James Holden’s retirement in December 1907, the position of Locomotive Superintendent was passed to his son Stephen Dewar, a decision which privately infuriated Frederick Russell, head of the Locomotive Design section at Stratford Works, who felt the position should have been offered to him. And not without good reason, for he was directly responsible for many of the designs attributed to James Holden such as the P43 4-2-2 Single, the famous Claud Hamilton 4-4-0 and the infamous Decapod 0-10 0T. However, nepotism won the day, and S.D. Holden took up the position in January 1908. In the end it worked out for the good; Stephen Dewar’s tenure was short and his contribution to locomotive design fairly light (although he patented many inventions while at Stratford), much of the work under his reign can be attributed to Chief Draughtsman E.S. Tiddeman, a long-term Stratfordian, who maintained continuity and ensured development of the Great Eastern style. Russell’s career took a different path – he was later promoted to Superintendent of Operations by General Manager Henry W. Thornton, and was instrumental in devising and implementing the famous suburban Jazz services.

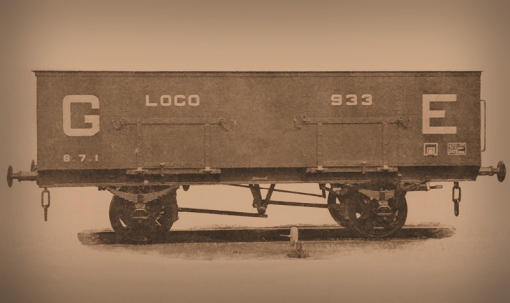

The Y65 Class

The last of James Holden’s revised version of the Worsdell M15 class was released to traffic on 18th June 1909, a full eighteen months after his retirement. Holden Sr. had left the Great Eastern Locomotive Department in a tremendously strong condition, and it wasn’t until 20th July 1909 that the first locomotive built under Stephen Dewar’s tenure was put into revenue-earning service. The Y65 class 2-4-2Ts were intended to both replace the last of the pre-Worsdell o-4-4 tanks class and to free up for other duties the rusticated members of the E22 class which pottered up and down the lightest of GE branchlines.

The prototype Y65 no.1300 posing in the photographic French grey (the ultramarine undercoat) livery with black borders and white lining. Most of the features mentioned in the main text can be seen; the brass-rimmed stovepipe, the dome on the back ring of the small boiler, the four-column Ramsbottom valves over the firebox, the large cab and huge quantity of glass – the tops of the front and rear windows following the profile of the high-arc roof, the brass ventilator, cab doors and coal rails on the bunker. Photo ©Public Domain

Letter Account Y65 consisted of two engines, and following on from the introduction of no.1300, no.1301 was released to traffic six days later on 26th July 1909. It’s certain that James Holden followed the career of his son, so must have looked on with amazement at the non-standard nature of this first locomotive which was an anathema to his legacy; a smorgasbord of old, new and seeming indecision. The uniquely sized 15” x 22” cylinders were driven by Stephenson’s link valve-gear with slide valves in a geometry similar to the T18 class, the non-standard small diameter boiler measured just 3′ 11½” over the clothing and was pressed to a working pressure of 160p.s.i. With 3’6″ radial and 4′ 10″ driving wheels, the engines’ nominal tractive effort was 11607 lbs.

Stylistically the Y65s were a scaled-down M15 crossed with an E22 and topped-off with a capacious (some might say disproportionately large) high-roofed cab, mirroring the Great Eastern Railway’s express and goods locomotive policy of the new century, and set a precedent for future tank engine designs. These small radial tanks quickly became known as the ‘Crystal Palaces’ due to their not inconsiderable acreage of glass.

The water capacity of the small side tanks was 1000 gallons and the bunker held just two tons of coal. The Worsdell-style dome was seated on the rear rather than the front ring of the boiler, and it’s difficult to understand the reason why four-column Ramsbottom safety valves were fitted when Stratford had always been – and would continue to be – satisfied that two-column valves were sufficient on boilers rated up to up to and including 160p.s.i. This anomaly was compounded by placing the valves over the firebox, in the manner of the two-column type, and implies that any safety concerns didn’t stretch as far as having the fireboxes stayed. The chimney was also unique, a kind of halfway-house comprising of a standard GE steel- fabricated stovepipe to Dia.1 with a brass rim of the type fitted to the contemporary large passenger engines. The Westinghouse pump and ancillary equipment, continuous handrails with integral Holden blower, cab controls, 1882 parallel-shank buffers, and whistle, et cetera, were all standard GER fittings.

Having done the rounds on the lightly laid branch lines of East Anglia, many Y65s ended up back in the London District, several of which were converted for compressed air operated push-pull services. No.1304 was the second fitted with the equipment which was based on the LB&SCR auto gear. The converted Y65s had a second Westinghouse pump fitted to the front of the LHS tank along with extra Westinghouse hose connections and a couple of electrical connections on the rear bufferbeams, one of the latter can be seen running along the rear of the valance to the cab door. For the auto services increased coal capacity was needed, so an extra four rails have been added to the bunker. No.1304 stands at Seven Sisters in 1921 in a very tired and grubby blue livery. Most Great Eastern locomotives had by this time been repainted in the wartime grey livery after Stratford’s stock of blue paint had been requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1915. Curious to see the front RH buffer is of the 8-bolt tapered variety, while the LH buffer is still the old 1882 parallel type. The arch-topped front and rear windows of the A67 batch differentiate between the majority of the class and the two prototypes. Photo ©Public Domain

New features which would become standard on future GER tank engines included a brass ventilator at the top of the front weatherboard, and half-height coal bars to protect the large rear windows. Two coal rails were fitted from new to bring the coal capacity up to 2 tons, S56-style cab doors increased the comfort of the crew, and intriguingly, as the class clearly wasn’t intended for London District duties, destination brackets were fitted to the smokebox door and bunker rear.

As nos. 1300 and 1301 were being built, an order was put in for a further ten locos, and nos. 1302 – 1311 to Order A67 were released to traffic between 2nd November 1909 and 28th January 1910. This new batch of radial tanks were identical to their two predecessors with one exception; whereas the top of the front and rear windows on nos. 1300 and 1301 followed the contour of the roof, those on nos. 1302 – 1311 were the same shape as the windows on the cab side sheets.

The class were initially allocated across the GE system and sub-shedded at Buntingford, Saffron Walden, Ramsey, St Ives, Stoke Ferry, Aldeburgh, Hadleigh, Braintree and Maldon. Much has been written on the unpopularity of the class, but I believe the majority of this stems from rehashing the offhand nature of their entry in the RCTS Vol.7 (1964). Earlier histories such as Aldrich (1944) had nothing bad to say about them, simply remarking that they would have been improved if rebuilt with a larger boiler.

On release to traffic at the end of 1909, no.1302 – the first of the A67 batch – was sent to Buntingford, replacing no.1301 which was allocated to Colchester for working to Walton. Locomotives shedded at Buntingford were fitted with a small steam-raising stop valve so that at night they could operate a pump to raise water from a nearby well to refill the supply tank. This might account for the small ladder on the side of the boiler. A conical re-railing jack rests on the tank top. Despite being in the suburban timetable, there were never any destination boards produced for Buntingford. Photo ©Public Domain

Indeed, at Buntingford, the only allocation within the Stratford district and which hosted no.1301 from its release to traffic in July 1909 until replaced by the newly-constructed no.1302 in December of that year, the class proved to be very popular. Aside from the crews’ appreciation of the covered footplate, their ability to haul eleven six-wheeled coaches over the relatively steep gradients of the tortuous 13½ mile long branch with ease earned them their approval. Neither was this feat unusual; in later years Frank E. Wilson witnessed one of the class haul a pair of Gresley Quint-Art sets from Palace Gates to Liverpool Street and the smartly-timed service to Enfield.

In April 1913, no.1302 was sent to Southend to trial two-carriage trains in the newly-expanding residential area of Southend, stopping at a number of proposed halts – a precursor to the auto-train trials the following year. The experiment was short-lived and no.1302 is seen here later the same year back in the East End on a Canning Town service with six-four-wheeled suburban carriages. The two green discs with white rims indicate the train originated at Victoria Park. Photo ©Public Domain

It’s also interesting to note that the three remaining pre-Worsdell 0-4-4T classes they were supposed to replace remained in service and continued to be withdrawn at a slow pace, the last of which survived until the end of 1913. Concurrently the Y65s began to appear on services in the Stratford District, some of which would later include the Great Eastern’s early push/pull services.

Modelling the Class

Connoisseur Models once produced a 7mm kit of the class (strictly speaking the A67 batch), and I was fortunate enough to buy the penultimate one before they all sold out. I was going to run it under the same excuse I have included the E22 class – i.e. occasional through trains from Buntingford, but my self-imposed temporal constraints have now put paid to that idea. There is, however, a strong possibility that No.1302 will eventually surface elsewhere in the Basilica Fields meta-universe.

I have to admit I’m rather fond of this class and its quirky style, and for me their introduction heralded the end of all that had gone before; La Belle Époque of the Great Eastern Railway had come to an end and nothing would be the same anymore. Stratford was entering a modern mechanised age where there was no place for the breathtaking, bewitching, beguiling, or beautiful; new locomotives appearing from the Works would now be big, bold, brash and brutish.

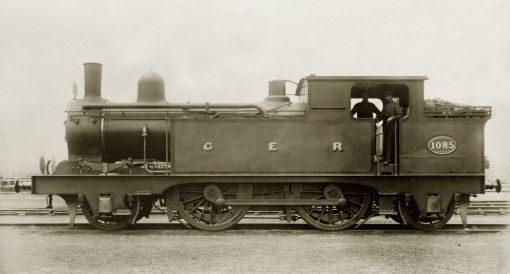

The G69 Class

Increased demand on the London outer suburban services by the end of the Edwardian period prompted the need for more frequent and heavier trains. With the exception of the single experimental 12-wheeled bogie suburban carriage set on the Enfield line, all suburban trains were still made up of close-coupled 4-wheeled carriages built between 1885 and 1905. During the first half of 1910, drawings of eight- and nine-coach sets of 48′ 3″, 50′ 0″ (reflecting the design of main line stock) and 54′ 0″ long (twice the length of the 4-wheelers) eight-wheel bogie carriages were prepared to determine the best way forward.

One warm Sunday in June on Brentwood Bank, no.63, resplendent in photographic grey livery, poses with the first of the new suburban bogie sets for the Loughton – Epping service. The large cab looks well-proportioned on these larger 2-4-2Ts with their high tanks and busy boilers. The four-column safety valves in the forward position and the parallel brass-rimmed chimney are prominent. The carriages are as follows: Dia.542 bk3rd no.333, Dia.236 1st/3rd composite no.7, Dia.104 1st no.10, Dia.300 2nd no.92, Dia. 300 2nd no.94, Dia.300 2nd no.97, Dia.237 1st/2nd composite no.6, Dia.542 bk3rd no.334. The set was close-coupled with a break point between seconds nos.94 and 97. Photo ©Public Domain

By the end of the year Stratford had settled on eight-carriage 54’0″ sets to the same design as the contemporary 50’0″ main line stock. These were designed to carry 808 seated passengers with up to half as many again standing, and, crucially, weighed 50 tons more than the comparative 4-wheeler sets. Four sets were completed in 1911 and a further ten were in service by 1914, all performing duties on the Loughton – Epping – Ongar line. Of course, the increased weight of the trains required more powerful locomotives and Stephen Holden chose to dust off his father’s revision of Worsdell’s M15 design, which had proven to be both reliable and capable for many years, and develop it for modern requirements.

The first of two batches of ten, numbered 61-70, formed Order G69 and were released to traffic between 3rd May and 30th June 1911. They took their numbers from a Neilson & Co.-built batch of Adams’ London Suburban 0-4-4 tanks, the No.61 class, which had been delivered in 1875-6, the last of which had already been added to the duplicate list and prefixed with a cipher.

No.61, the first of the class, poses newly shopped in ultramarine blue, the vermilion lining not visible due to the limitations of the orthochromatic emulsion. Three coal rails were fitted from new, and unlike similar photographs of new G69s posed in grey, the running number is not repeated on the lined-out toolbox. Photo ©Public Domain

The second batch of ten to order A71 and numbered 1-10 entered revenue-earning service later in the year between 17th and 29th November. The 2-4-2T was the second Great Eastern locomotive to carry the prestigious No.1 works plate, the previous bearer being the first of S.W. Johnson’s 2-4-0 ‘Little Sharpies’ built in 1867 and remarkably still in service (and, incidentally, the last to be withdrawn in 1913), having been put on the duplicate list on the 1st January 1911 and its running number prefixed with a zero.

The G69 class were fitted with a brand new type of boiler, the same size as the M15s, but pressed twenty pounds per square inch higher at 180p.s.i. They had a sloping rather than a flat grate and were fitted with four-column Ramsbottom valves placed over the back ring of the boiler. Visually the biggest impact was the addition of the high-arched Y65-style cab (or, strictly speaking, the A67 cab) which appeared rather handsome and well-proportioned on these larger engines. There was a 10cwt reduction in coal capacity to 3 tons, but slightly higher side tanks gave an increase of 250 gallons to 1,450 gallons.

The engines had parallel built-up chimneys (and as passenger engines were topped off with brass rims) of a visually similar design to the tender engines introduced from 1898, with the exception that the base was slightly shorter. However, internally the chimneys were very different; all the chimneys on the larger engines, with the exception of Decapod, were tapered inside the casing and had cast iron petticoats (designated Diagram 2), whereas those on all the tank engines from G69 onwards were parallel inside (designated Diagram 3).

Eight days after entering service, no.61 is photographed on 21st May 1911 at Liverpool Street with the unique 12-wheel bogie suburban set (with eight wheel bogie brake thirds at each end) built in 1900 for the Enfield line and described in the entry on the R24R class. At least engineers standing on the running plate testing the performance of the boiler had tall timber shelters by this time, their predecessors twenty years earlier had no such luxury, just a low shelter to stop them from falling off. Photo ©Public Domain

All twenty of the Westinghouse-braked engines were fitted with condensing apparatus for the London suburban duties. However, unlike the M15s, the vent pipes were situated on the tank tops outside the cab, pre-empting their position on the future L77 class 0-6-2Ts. One other visible difference contributed to the busy nest of rods and pipes on top of the boilers; on the M15 160p.s.i. boilers, injector steam cocks were mounted on top of the boiler back inside the cab, but on the 180p.s.i. boilers the same cocks were mounted near the dome with control rods leading back to the cab.

Modelling the Class

Laurie Griffin’s F6 kit is the LNER classification for the GER G69. It’s an upgraded version of the old Shedmaster kit, and with care produces an accurate model.

The M15R Class

With the first ten G69s entering service, the opportunity was taken to up-rate a number of the 1903-1909 series of M15s with the sloping-grate G69 180p.s.i. boiler, and to differentiate these locomotives from the earlier 160p.s.i. flat-grate rebuilds they were assigned the classification M15R or M15Rblt.

No.110 was rebuilt as an M15R in August 1913. The LH side injector valve is visible behind the dome, and the rimmed parallel chimney and four column safety valves in the forward position distinguish it from the M15 class engines. By the time of this photo, the old flat-dished smokebox door, which was prone to heat distortion, has been replaced with Alfred Hill’s heavier type. Eight-bolt tapered buffer housings have been fitted. Photo ©Public Domain

As noted above, the first G69, no.61 was released to traffic on 3rd May 1911, and one month later M15 no.104 entered Stratford Works for a General overhaul and to be rebuilt. Four months later, on 9th October, both it and no.103 (which had come into Works two days after no.104) re-entered revenue-earning service as M15R class engines, the first of an eventual 30 members of the class. The vast majority of these rebuilds were completed over the next three years, and all bar one completed by 1916. No.188 finally re-entered service in June 1920 having languished in the sidings at Stratford since the end of the Great War.

Visibly there were few differences between the M15R and the 160p.s.i. M15s; the M15Rs had sloped instead of flat grates, G69-style parallel chimneys with brass rims instead of stovepipes, four-column safety valves seated on the back ring of the boiler instead of two column valves over the firebox, whistles mounted on the cab front instead of the valve seat, and the injector steam cocks mounted behind the dome instead of inside the cab. The rebuilds retained their 1200 gallon side tanks and 3½ ton capacity bunkers.

No.96 was converted to M15R in October 1911 and still carries the original smokebox door and 1882 parallel buffers. The RH injector steam cock on the boiler with the long control rod and pipe is is much more visible on this non-condensing member of the class. Somewhat intriguingly it has what appears to be a steam-raising stop valve in front of the dome, which suggests it may previously have been sub-sheded at Buntingford, though I have no record if it there. Photo ©Public Domain

Twenty of the rebuilds were non-condensing engines, but six of these gained the apparatus during their rebuilding which indicated their anticipated duties. In his article ‘Improving Buckle’ Lyn Brooks suggests that the only mechanical difference between the M15R and G69 classes was the size of shim placed between the eccentric straps and rods in the link motion.

Visual differences between the M15 and M15R classes soon began to blur, a process which years later would eventually end with just the running number giving away the classification; in 1913 it was decided that engines and boilers were no longer paired for life, and the following year, once production of the 160p.s.i boilers ceased, G69 sloping-grate 180p.s.i. boilers began to be fitted to the 1903-1909 series of M15s with new four column valves de-rated to 160p.s.i. and placed in the forward position over the back ring. With the exception of No.798, which received a brand-new but de-rated 180p.s.i boiler in 1920, 160p.s.i boilers removed from the 1903-1909 series were set aside for surviving members of the three batches of M15s built during the 1880s – the first three of which had been withdrawn in 1913.

With the imposing Skinner Street bridge behind, 2-4-2Ts contribute to the smog as they wait their turn at Liverpool Street station. At the back a C32 class, at front right an unidentified 1903-1909 series condensing M15 class and on the left no.76, a condensing M15 with a 180p.s.i. boiler with four-column safety valves in the forward position and de-rated to 160p.s.i. Neither the East nor West Side signal boxes had a full view of the domain they controlled so each had an extra ‘observation box’ located at the ends of platforms 4/5 and 14/14 respectively. The driver of the unidentified M15 lets off a sharp whistle and is looks towards the East Side OB indicating he is ready to move onto the waiting carriages in platform 13 for the next down outer suburban service. Photo ©Public Domain

At 53t 19cwt the M15Rs weighed 2 tons 6cwt heavier than the M15 class but 2½ tons lighter than the G69 class, although the tractive effort was identical to the latter.

Modelling the Class

The LNER classification for the GER M15R was F5 and both Connoisseur Models and Laurie Griffin can supply kits for the class, though third party castings from Laurie, Ragstone or Alan Gibson would be needed to backdate the kit to the GER period.

M15 with G69 Boiler and Large Cabs

In 1912 a hybrid conversion resulted in this rather convoluted classification for two locomotives, nos. 789 and 790. Post-rebuild they were to all intents and purposes members of the M15R class, retaining their original 1200 gallon side tanks and 3½ ton capacity bunkers, but were fitted with G69 cabs. Both had been built as non-condensing M15s in 1904 under Order D58 (no.790 being the second member of the class to carry that number, the previous bearer being renumbered no.800 in 1892), and both received condensing apparatus on being rebuilt. One interesting facet of this hybrid class was that like the M15 and M15Rs the condensing vent pipes were located inside the cab so projected through the roof. However, whereas the other locomotives had a sizeable stub protruding from the shallow-arc roof with the top of the pipe cut away horizontally, the top of the vent pipes on nos.789 and 790 were almost flush with, and contoured to match, the profile of the G69 high-arc roof.

Hybrid no.789 looking very down-at-heel rests at Stratford. As can be seen, it is, to all intents and purposes an M15R with the G69 high-arc cab. From this angle the top of the condensing vent pipe can be seen almost flush with, and profiled to the shape of the roof. There’s an interesting riveted patch on the smokebox which I’ve not seen elsewhere. Photo ©Public Domain

It’s not known why nos. 789 and 790 were converted in this hybrid manner, but they brought the total number of conversions to thirty two.

One final, and somewhat intriguing comment about the M15-M15R and G69 classes is that the side tanks and bunkers had 2”x 2” angle around the bottom edges, flush-riveted to the running plate. The feature was common on earlier tank locomotives, but these and the T18’s were the only tank engines built after 1885 to retain the feature.

Modelling the class

Jim at Connoisseur Models sells an add-on pack of etches to convert his F5 kit into the F5/6 hybrids.

The other hybrid, no.790 also looking very scruffy, although apparently with a new or reconditioned smokebox and chimney. Although the GER classified these two engines separately, the LNER somewhat confused by their nature, lumped them in with the G69s and classed them F6. British Railways saw sense and later reclassified them both F5. Photo ©Public Domain

To round off the 2-4-2T saga, I suspect that no more than a handful of Great Eastern Railway locomotives were captured on film during the pre-Grouping period. However, In October 1920 M15R no.96 was fitted with the experimental Regan electro-mechanical train control system and underwent trials on the Fairlop Loop. In addition to the automatic stop device, the right hand side trailing radial wheel was fitted with a speed control. The Great Eastern had already trialled the Sykes (SYX) train control system on the Palace Gates and Ongar branches, fitting the control gear to G69 no.66, part of which was designed in-house and patented by E. S. Tiddeman. The Regan system didn’t find favour with the company and the trials progressed no further.

Fortuitously the rushes survive in the Pathé newsreel library, and an article on the trials was published in the November 1920 issue of The Railway Magazine, illustrated with photos, possibly stills from the film. The article notes that those present included the inventor Mr J. B. Regan, Mr J. H. Thomas M.P., various chief officers of the GER, signal engineers and experts from several railway companies, and representatives of the technical and general press.

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/unknown-celebrities-at-inauguration-of-new-train-l

It’s a fascinating snippet for not only the railway element of seeing a Great Eastern locomotive at work on home turf in this period, but in terms of fashion, especially the wide range of hats, from the Bowler and Homburg, to the Fedora, down to the various styles of flat caps, which, intriguingly, had begun to transcend social status. It’s lucky for the very confident Mr. Cholmondley-Warner standing in the 4-foot the Great Eastern used the Westinghouse brake and could stop on a sixpence…an H&S apoplexy in more ways than one!

Finally, the F5 Trust is building a working replica of no. 789, details of which may be found here.

References:

- GERS Journal no.6 – The Crystal Palace Tanks by Lyn Brooks

- GERS Journal no.103 – An Introduction to the GER Carriage Part 2 by John Watling

- GERS Journal no.129 – Updating Buckle Part 2 by Lyn Brooks

- GERS Journal no.146 -Carriage Building in 1911 by John Watling

- GERS Journal no.150 – The Locomotive Department in 1912 by Lyn Brooks

- GERS Drawings by John Gardner

- RCTS Locomotives of the LNER Part 7.

- Yeadon’s Register Volume 39

- Locomotives Illustrated no.116

- The Buntingford Branch by Peter Paye